Our view is that both risk appetite and risk tolerance are inextricably linked to performance over time. We believe that while risk appetite is about the pursuit of risk, risk tolerance is about what you can allow the organization to deal with. Organisations have to take some risks and they have to avoid others. The big question that all organizations have to ask themselves is: just what does successful performance look like? This question might be easier to answer for a listed company than for a government department, but can usefully be asked by boards in all sectors.

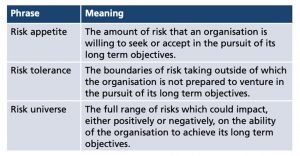

We believe that the appetite will be smaller than the tolerance in the vast majority of cases and that in turn will be smaller than the risk universe, which in any case will include “unknown unknowns”. Risk tolerance can be expressed in terms of absolutes, for example, “we will not expose more than x% of our capital to losses in a certain line of business” or “we will not deal with certain types of customers “. Risk appetite, by contrast, is about what the organization does want to do and how it goes about it. It, therefore, becomes the board’s responsibility to define this all-important part of the risk management system and to ensure that the exercise of risk management throughout the organization is consistent with that appetite, which needs to remain within the outer boundaries of the risk tolerance. Different boards, in different circumstances, will take different views on the relative importance of appetite and tolerance.

As an aside, it seems that the terms “risk appetite” and “risk tolerance” have deep associations with the financial services industry in some minds, and attempts to move non-financial services organizations in that direction might have been difficult. However, these words can be seen, for all intents and purposes, as being indistinguishable from the previous phrases. While many commentators see them as inseparable phrases, we focus predominantly on the concept of risk appetite in this paper as a way of providing guidance to directors and those tasked with advising directors on the requirements of the Code in so far as they relate to risk appetite and tolerance.

Risk appetite is a phrase that is widely used but frequently in different contexts and for different purposes. It is a phrase that for some people conveys poorly its meaning, and in respect of which the meaning is different for different groups of people. Based on the work that was undertaken in writing this paper it was clear that there is little certainty as to what the phrase means, but there seems to be almost unanimity that it could be, and indeed ought to be a useful concept, if only it could be properly expressed. Some people prefer other terms such as risk attitude or risk capacity. As far as we are concerned there is nothing fundamentally wrong with using any of these terms. Suffice it to say that in writing this guide we are taking a very pragmatic view: risk appetite is the most common phrase that we have come across, it is the one that was used by the FRC in the context of the draft Corporate Governance Code and therefore we would prefer to define this term in a way that begins to make sense for as many people as possible.

Given the lack of conformity about the meaning of the phrase, it is worth looking at the key standards on risk management, ISO31000 (ISO, 2009) and BS311001 (British Standards, 2008), to see what light they shed on the subject. Interestingly ISO31000, the international standard, is silent on the subject of risk appetite (focusing instead on ‘risk attitude’ and ‘risk criteria’), although Guide 73 (ISO, 2002) defines risk appetite as the “amount and type of risk that an organization is willing to pursue or retain.” Some people argue that ISO31000 is silent on the subject because it is neither a useful phrase not a meaningful concept. They, therefore, focus more on risk criteria. On the other hand, we believe that there is a benefit to exploring what we think is turning out to be a useful and meaningful concept.

The original BS31100 contained more detail. It defined risk appetite as the “amount and type of risk that an organization is prepared to seek, accept or tolerate” – very similar to Guide 73. The standard went on to define risk tolerance (bearing in mind that the definition of risk appetite includes reference to tolerating risk) as an “organization’s readiness to bear the risk after risk treatments in order to achieve its objectives”. The definition then includes a rider that states: “NOTE: risk tolerance can be limited by legal or regulatory requirements”.

Notwithstanding the regular appearance of risk appetite and risk tolerance in the same sentence (or definition in the case of BS31100) it is our belief that risk tolerance is a much simpler concept in that it tends to suggest a series of limits which, depending on the organization, may either be: a) In the nature of absolute lines drawn in the sand, beyond which the organization does not wish to proceed; or b) More in the nature of tripwires, that alert the organization to an impending breach of tolerable risks.

In conclusion, BS31100 provides some guidance on how to use risk appetite, but it does not (nor did it ever set out to) provide guidance on how to calculate or measure risk appetite, although the standard does suggest the use of “quantitative statements”, without further elaborating. It is interesting to note that the revised version of BS31100 has substantially removed references to risk appetite to bring it in line with ISO31000. This leaves something of a vacuum on the subject.

In practice, we have found that in many instances these terms are used interchangeably. We think that is conceptually wrong: there is a clear difference between the two. It is also worth noting that in the eyes of some commentators, risk tolerance is the more important concept. While risk appetite is about the pursuit of risk, risk tolerance is about what you can allow the organization to deal with. Without a doubt, there will be occasions when an organization can deal with more risk than it is thought prudent to pursue.

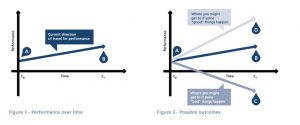

The difference can be illustrated in the diagrams at the bottom of this page. Figure 1 shows performance from the current time (t0 ) to sometime in the future (t1 ). Line AB shows the current expected direction of travel in terms of performance. Figure 2 shows that in practice this is subject to risks which, should they materialize, could result in performance along the line AC, or to opportunities (positive risks) which could result in performance along the line AD. The potential risk universe or the total risk exposure is shown by the difference between C and D. (see Figure 3). What is clear is that following line AC is not desirable. Less clear is that it might also be undesirable to follow line AD because pursuing it might throw up substantial additional risks. Consequently, there are some risk outcomes for which there is no tolerance, and moreover no tolerance for taking those risks. Moreover, since we are using the generally accepted concept of risk as being potentially positive as well as negative, that suggests that there is a range shown by the triangle AXY (See Figure 4), outside of which the organization will not tolerate exposure. This is risk tolerance.

On the other hand, our “appetite” for risk is likely to be shown by a narrower band of performance outcomes shown by the triangle AMN. Risk tolerance can therefore be expressed in terms of absolutes: for example “we will not expose more than x% of our capital to losses in a certain line of business”, or “we will not deal with a certain type of customer”. Risk tolerance statements become “lines in the sand” beyond which the organization will not move without prior board approval. Risk appetite on the other hand is about what the organization does want to do and how it goes about it. It, therefore, becomes the board’s responsibility to define this all-important part of the risk management system and to ensure that the exercise of risk management and all that entails is consistent with that appetite, which needs to remain within the outer boundaries of the risk tolerance.

While we have focused primarily on risk appetite, some entities (such as Government departments) may be more focused on risk tolerance. This in itself becomes a more complicated issue where the risk of insolvency (the ultimate determination of failure for corporates) is absent. Defining success and failure is therefore very important. This is an area where we believe further work is required. What is clear is that different boards in different circumstances will take different views as to which of these two concepts is more important for them at any given time.